Running a business today means paying a tax. Not to the government but to Google, Meta, Amazon and even your friendly local marketing agency.

I've managed hundreds of millions in digital ad spend. No matter if you are a global brand or a local florist, if you want customers at scale, you pay.

Like real taxes, the cost never disappears. It's been climbing for years. And just like real taxes, businesses rarely carry the burden alone. They pass it along. That is how the internet became “free.” We don't swipe a credit card to search Google or scroll Instagram. Instead we pay later, at checkout, in the hidden markup built into sneakers, deodorant, or meal delivery.

Who Really Pays

Ad budgets look like corporate line items. In reality, they show up in the household budget. When a brand spends 20 percent of its revenue on advertising, that cost isn’t absorbed by shareholders. It rolls into the sticker price. The next time you wonder why your favorite cereal costs more, remember, part of that box paid for a search ad.

The hidden nature of the ad tax is what makes it powerful. Buyers rarely notice it, because it blends into retail prices. But collectively it represents hundreds of billions of dollars transferred each year from buyers to ad platforms.

Where the Money Goes

Government taxes fund public goods. Roads, schools, defense. The ad tax funds private ones. Data centers, AI training clusters, logistics networks, shareholder buybacks. Some of this creates real value, like faster delivery or better recommendations. Some fuels projects nobody voted for, like a multibillion dollar metaverse bet.

It's not inherently bad. The reinvestment has helped build much of the infrastructure that makes modern commerce possible. But it is worth asking whether the balance is shifting.

The Extreme Case: Amazon

If Google and Meta are tollbooths, Amazon is the entire highway system.

To sell on Amazon you almost have no choice but to use Fulfillment by Amazon for 2-day Prime shipping. That brings storage, packing, and delivery fees. Add in referral fees that run ~10 percent. Then layer on advertising, which has quickly become the largest toll of all.

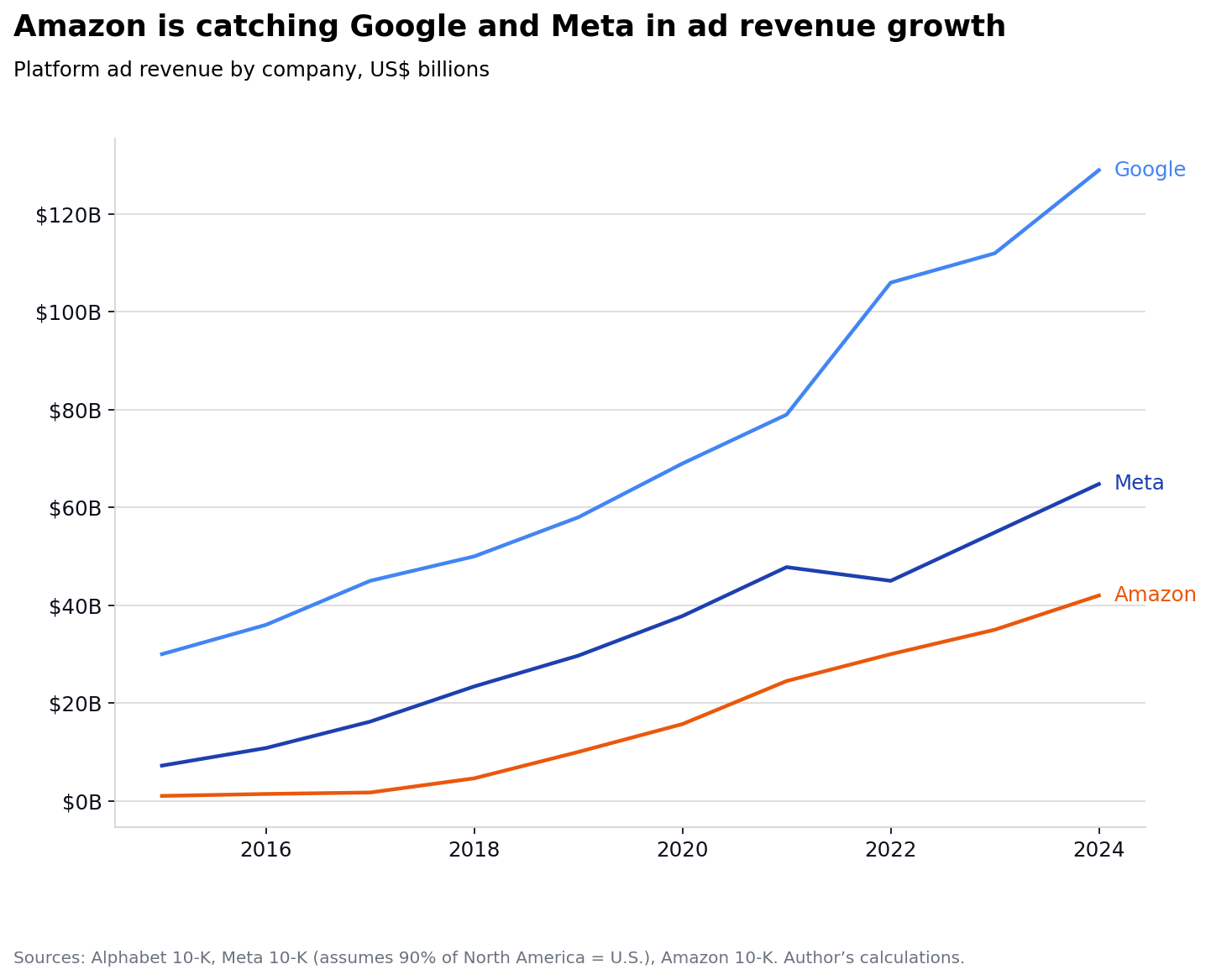

In Q2 2025, Amazon’s ad revenue grew 22 percent year over year to $15.7 billion. At that pace, ads alone will soon surpass $100 billion annually. Their growth is faster than Google’s and Meta’s.

The end result is that a seller can easily see 30 to 50 percent of gross revenue flow back to Amazon before covering product costs. What began as an online book store has become a vertically integrated system of taxes on third-party sellers. Not a bad business.

The Ad Tax in the Economy

Amazon’s rise isn’t an isolated story. Together, the three major platforms have transformed advertising into a macroeconomic force.

Amazon is catching Google and Meta in ad revenue growth

Since 2015, their combined ad revenue has grown fourfold. At nearly $250 billion a year, the “ad tax” is no longer just a business expense. It shows up in the national economic metrics.

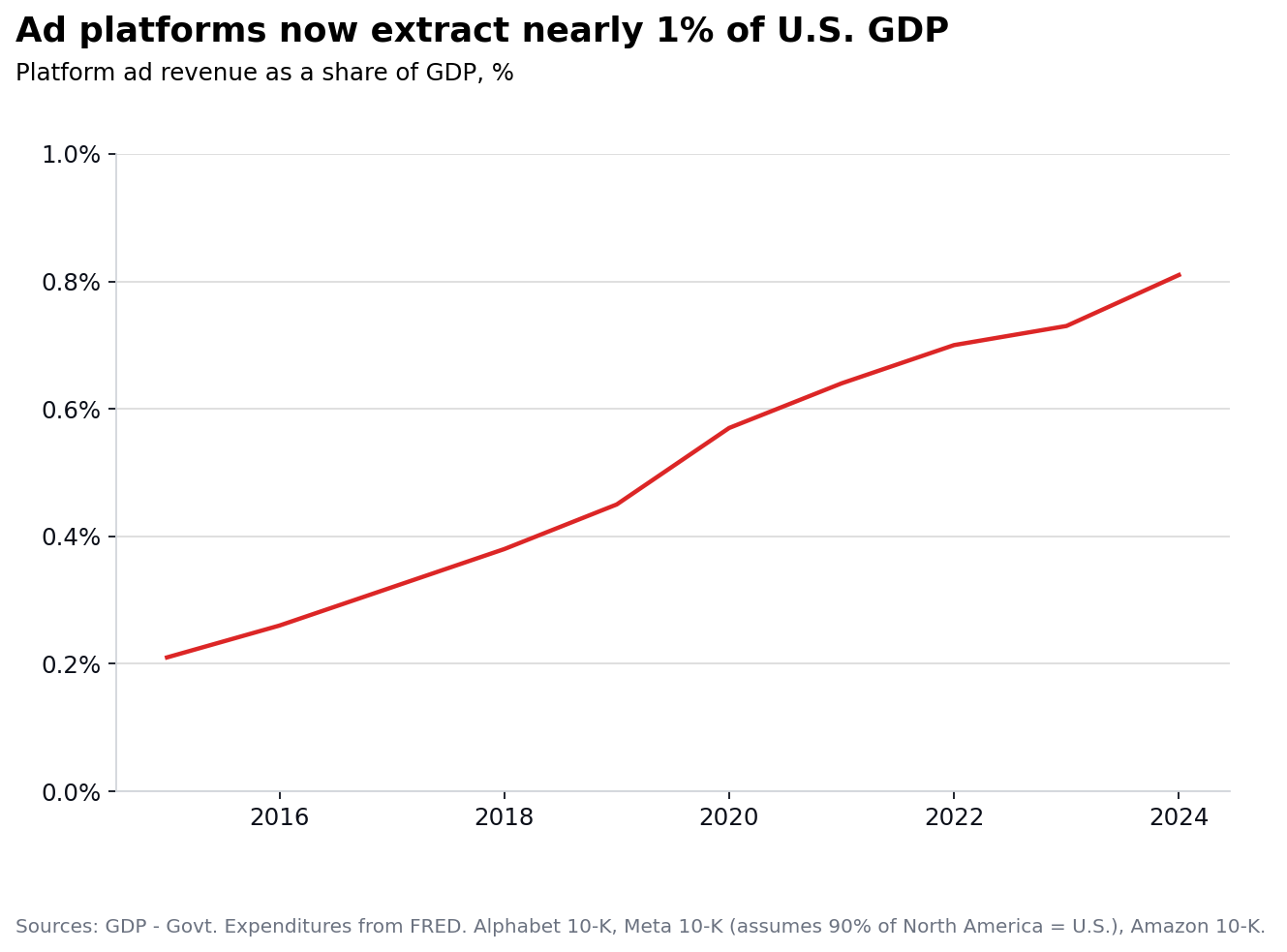

Ad platforms now extract nearly 1% of US GDP

Today almost one cent of every dollar of US non-government output flows through ad auctions. That is not trivial. It means platform incentives ripple through the entire economy, shaping what gets built, shipped, and sold.

A Private Tax System

This creates a paradox. US politicians often argue about keeping corporate tax rates low in the name of competitiveness. Yet we have built a far larger private tax system, enforced by algorithms and ad auctions, that quietly extracts nearly as much as the annual corporate tax income.

The difference is where the money goes. Washington debates how to spend tax dollars. Platforms allocate based on boardroom priorities. Sometimes that means infrastructure that benefits users. Other times it means stock buybacks.

The Consumer’s Vote

Consumers still hold power. Every purchase is a vote. If Amazon continues to translate ad revenue into faster shipping and cheaper delivery, or if Google and Meta reinvest in better discovery and tools, the ad tax feels tolerable. It funds progress.

The risk is when reinvestment slows. If platforms pocket the gains without building new capabilities, the tax starts to look less like the price of progress and more like rent.

Owning the Tollbooth

For businesses, the ad tax is unavoidable. For consumers, it is invisible but constant. For investors, it is something different altogether. A direct claim on US (and global) consumption.

When you hold Amazon, Google, or Meta, you are not just buying technology companies. You are buying a piece of every purchase routed through their tollbooths. As ad costs rise, that flows into platform revenue. As reinvestment improves logistics or discovery, that value flows back to consumers. And eventually, when growth slows, it flows to shareholders through dividends and buybacks.

In that sense, the ad tax is not only the hidden cost of the internet. It is also the hidden mechanism that lets investors capture both sides of the transaction. Consumer benefit and investor return.

The tollbooth is permanent. To own it is to own a slice of the global consumer.